Testing practices

At Georgian, each course outline lists the type and weighting of evaluation methods. Tests, quizzes and exams are common and significantly weighted evaluation methods.

Considerations for evaluation

Georgian’s Office of Academic Quality provides the following considerations for evaluation:

- Provide students with evaluation opportunities at regular intervals throughout the term.

- Provide a minimum of two evaluation categories and three evaluation opportunities per course.

Tests

By definition, a test is a planned, periodic assessment. Tests can include multiple choice, short- and/or long-written answers and are commonly set within class periods. From a course outline perspective, it is reasonable to include quizzes and/or exams in this category definition.

Quizzes

A quiz is a short test that can be announced or unannounced and delivered in or out of class. Typically, a quiz is not given a major weighting in course evaluation.

Examinations

An examination is a cumulative evaluation at fixed points in the semester, such as mid-term and end of term. It includes comprehensive final exams which assess the students’ understanding of topics covered throughout the full term. Course outlines should specify if a comprehensive exam is included.

Material adapted from Georgian College. (2022, May 30). Course Evaluation Categories. Retrieved August 16, 2022.

Benefits, disadvantages and considerations of testing

According to Roediger et al (2011), there are 10 benefits to using testing in education. In the article, the authors state, “If students are quizzed frequently, they tend to study more and with more regularity. Quizzes also permit students to discover gaps in their knowledge and focus study efforts on difficult material; furthermore, when students study after taking a test, they learn more from the study episode than if they had not taken the test.”

The authors suggest that testing:

- aids later retention

- identifies gaps in knowledge

- causes students to learn more from the next learning episode

- produces better organization of knowledge

- improves transfer of knowledge to new contexts

- can facilitate retrieval of material that was not tested

- improves metacognitive monitoring

- prevents interference from prior material when learning new material

- provides feedback to instructors

- frequent testing encourages students to study

It has been suggested that testing motivates students to put more effort into their studying (Zimmer, 2021).

There are disadvantages to using testing to assess students (Benitez, 2019; Zimmer, 2021). They:

- can cause high stress/anxiety reactions in some students

- can have negative effect on student motivation (especially for students with poor performance)

- use class time and may result in teaching to the test at the expense of other teaching and learning opportunities

- may lead to superficial rote learning and/or retrieval induced forgetting

- may lead to students’ creation of erroneous knowledge through the construction of the test

- do not provide an overall picture of student’s achievement or abilities as results are based on one moment in time

- may lack authenticity and real-world application of learning

- can have inherent bias towards students with language or cultural barriers, or disabilities

In addition, questions styles can have their own disadvantages (Weimer, 2018) including testing literacy skills rather than content understanding, can encourage guessing and memorization and may limit scope of exam questioning resulting in devaluation of other content. When test questions do not align with material taught and how it was taught, reliability and validity errors appear and can be used to question test results and grading methodology (Zimmer, 2021).

Faculty typically have some flexibility when designing their course evaluations.

When deciding to use a test, quiz or exam, here are some questions to consider (Queens University, 2021):

- Will this assessment method allow you to understand how well students are achieving learning outcomes?

- What needs to be graded versus ungraded?

- What type of assessment is sufficient (e.g. can a quiz be used rather than a test, a test rather than an exam)?

- What can be done in and out of class?

- How much time will the grading take?

- Are course assessments manageable in terms of student and faculty workload?

- What are the demands on your students in their other courses?

- Can the assessment be designed to support all learners?

- Does the assessment encourage growth in learning rather than performance?

Answers to these questions will help guide the choice of quiz, test or exam, the style and method of delivery, as well as the types of questions within the assessment.

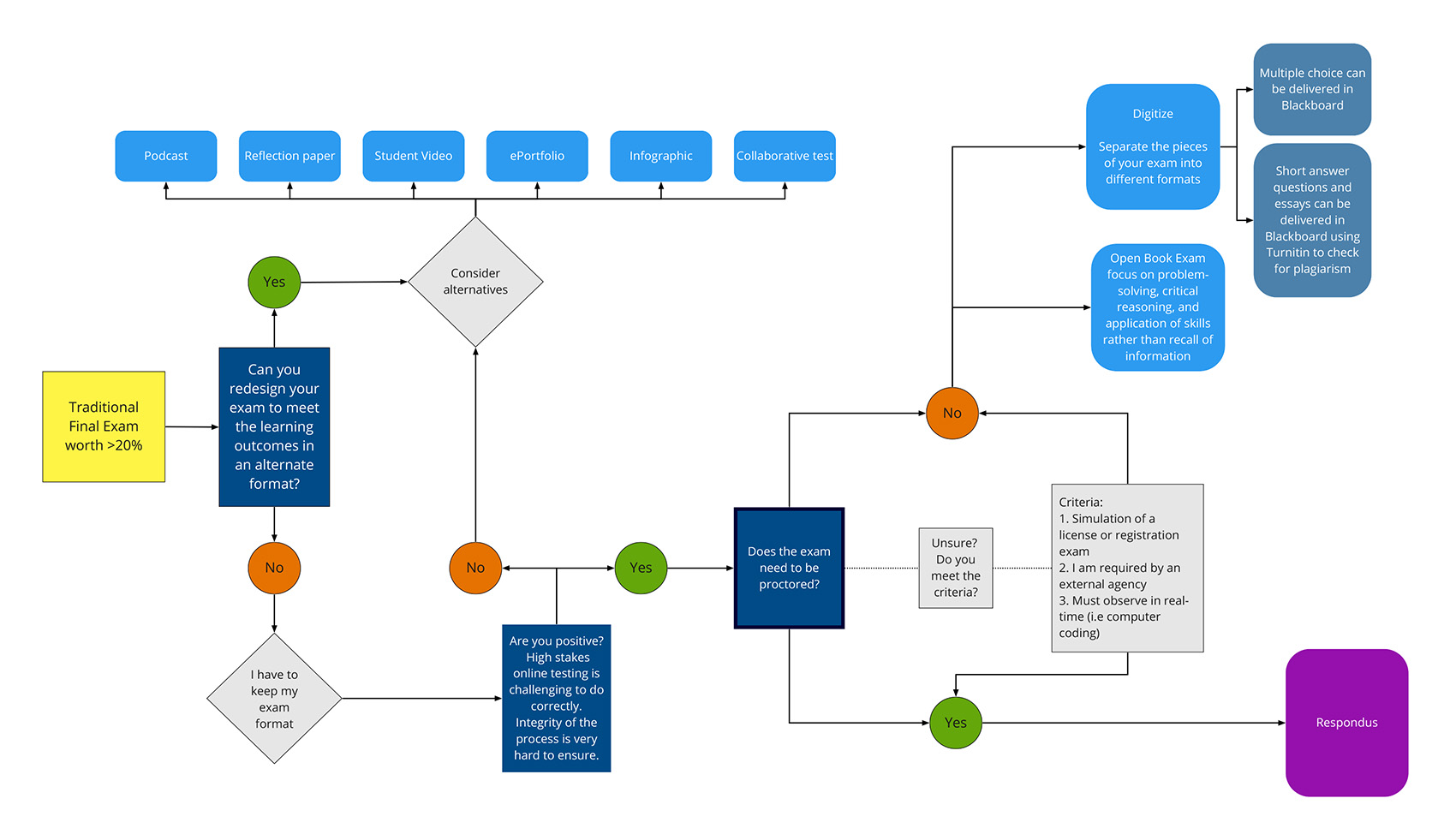

The Centre for Teaching and Learning (CTL) at Georgian has created this decision-making flow chart to help faculty make evaluation method decisions for use in the online environment. In particular, traditional final exams worth greater than 20 per cent are explored. Alternative assessment options, open book exams or independently written exams and proctored exams are potential options. Faculty wishing to further explore proctored exams should consult their associate dean or manager.

Benitez, J., MD. (2019, February 20). Retrieval Practice: 10 benefits of testing. ALiEM. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Karpicke, J. D. (2012, October 12). Testing Can Be Useful for Students and Teachers, Promoting Long-Term Learning. Association for Psychological Science – APS. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Queens University. (2021). Sample Assessment Methods. Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Roediger III, H. L., Putnam, A. L., & Smith, M. A. (2011). Ten Benefits of Testing and Their Applications to Educational Practice. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 1–36.

Saucier, D. A., PhD. (2022, February 8). Five Reasons to Stop Giving Exams in Class. Faculty Focus | Higher Ed Teaching & Learning. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Weimer, M., PhD. (2018, October 5). Advantages and Disadvantages of Different Types of Test Questions. Faculty Focus | Higher Ed Teaching & Learning. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Zimmer, T. (2021, November 5). The Effects of Standardized Tests on Teachers and Students. The Classroom | Empowering Students in Their College Journey. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Creating test-like assessments

Formative assessments, such as quizzes, can be used to support student learning through a quick glimpse into their understandings or misunderstandings before a summative assessment (such as a test or exam). Refer to the assessment fundamentals webpage. Formative assessment can be graded or ungraded. If graded, it is typically low stakes marks and weighting. Consider offering opportunities for students to practise formative assessment, retake assessment to improve success or use the best x of y scores for grading formative assessment. The key element for all formative assessment is the opportunity for students to practise their skills or test their knowledge without high stakes pressures and with opportunity for feedback and improvement prior to higher weighted assessments (Queens University, 2021a).

Summative assessments are higher weighted assessments used at the end of a learning cycle or unit to evaluate students learning against the expected. These are always graded. Tests and exams are typically considered summative assessments (Queens University, 2021a).

When designing a test, quiz or exam, it’s helpful to revisit the course learning outcomes to ensure the assessment is focused on evaluating the key learning of the course. Review the Integrated Course Design (ICD) model, which shows the integration between learning outcomes, teaching and learning activities and formative/summative assessment.

When picking a method of assessment, consider what learning outcomes are hoped to be evaluated using the assessment. From there, select teaching and learning activities that support the students’ learning the content and provide scaffolding opportunities for the type of assessment. For example, on a test, students are expected to analyze a case study scenario. A scaffolding opportunity could be completing case studies in class as a learning activity. Then, completing a case study as a quiz or other formative assessment where there is opportunity for feedback (Queens University, 2021c).

Creating good test-like assessments takes time. In the end, both faculty and students want the assessment to be fair. This can mean different things to different stakeholders. Consider the below items when writing an assessment (Queens University, 2021b).

Does the assessment support students’ improving their learning? This is usually accomplished with formative assessments, which are designed for learning. With summative assessments, improving learning may look like informing the faculty and students of what has been learned, where there is strong understanding of concepts and where gaps exist. Summative assessments can be used as a tool to motivate students to apply and demonstrate their knowledge.

The results from an assessment should have meaning and be reliable in that similar results are seen with each administration. The assessment should be consistent and an accurate reflection of student performance. Administering the test under suitable conditions is important to support reliability.

Assessments are designed to assess students’ ability to meet the course learning outcomes. Alignment with course content and assigned learning activities is important. Testing content not included in the course should be avoided.

Assessments should be designed so that students are not disadvantaged based on factors such as culture, gender, socio-economic background and personal experiences (amongst others). Assessments should not discriminate, nor favour, any group of learners. Students are not a homogenous group and assessments should strive to provide different opportunities for students to demonstrate their learning. With grading, students should be assessed on the merits of their work and not based on any impression we might have of them, nor on their performance on previous assessments.

Students approach assessments differently based on graded or ungraded, low stakes weighting or high stakes weighting. Having clear written statements prior to assessment help with this transparency. Sharing expectations with a whole class conversation and written details also helps. Clear and complete directions for the assessment are also key for transparency.

Support for writing assessment questions

For support in writing multiple choice, multiple answer, true-false, matching and short-answer assessment questions, see these suggested resources:

- BCIT Learning and Teaching Centre. (2010). Developing Written Tests. British Columbia Institute of Technology.

- Cloud County Community College. (n.d.). How to Write Better Tests.

- Shaw, A. (2020, January 31). Writing Quiz Questions. Center for Teaching and Learning | Wiley Education Services.

Queens University. (2021a). Assessment Types: Diagnostic, Formative and Summative. Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Queens University. (2021b). Fair Assessment Practices. Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Queens University. (2021c). Revisiting Learning Outcomes. Teaching and Learning in Higher Education. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Testing alternatives to formal closed-book tests/exams

High-stakes testing requires students to offer their best performance at a specific point in time. These environments can create situations for anxiety, high stress and ultimately result in poor performance. Test anxiety interferes with a student’s ability to recall information about the material being tested, resulting in poor performance. In addition, factors such as poor study skills, improper test preparation, language difficulties and poorly written questions can lead to poor performance and, potentially, increased error in test validity (Cantwell et al., 2017).

There are many alternatives to using formal closed-book testing type assessments. Below are some suggestions as to alternatives that still involve test-like questions, but aim to reduce high-stress, high-anxiety and poor-performing circumstances.

Concept tests are small, short, informal tests that focus on key concepts. A quiz would be considered a concept test. The primary purpose is to get a snapshot of the current understanding of the class. To support student success, consider having multiple quizzes or end-of-section/end-of-chapter tests throughout the semester instead of higher stakes mid-terms or finals. If there is no requirement for a comprehensive exam, consider using quizzes and a project or alternative assessment (Carnegie Mellon University, 2022), (UC Berkeley, 2022).

In addition, consider the use of quiz mastery which allows students to repeat or resubmit an assessment. The number of attempts can vary. In some cases, a second attempt is offered to students with their results being the best score or average of both scores. Other times, the purpose of the quiz makes unlimited attempts a reasonable offering.

Grading of concept tests or quizzes will vary. It may make sense to score results based on correctness. Other times, grading for completeness may be enough (e.g. is it done or not done). More importantly, it’s the feedback to students (not the grade) that will encourage their future learning and review processes.

If a formal test is required, consider allowing students to design their own reference sheet to use while writing the test. This encourages students to spend time reviewing course material and can help reduce test anxiety. Faculty can set the size of paper, have the reference sheet submitted for approval, etc. (Kennette, 2019).

An oral test format has students meeting with faculty one-on-one or in small groups for a set timed discussion. The discussion should be based on a previously shared list of topics, problems or case studies. Students should be given direction and rubric to guide their preparations. Typically, students are assessed for (University of Houston – The Honors College, 2022):

- knowledge of course material

- originality of thought

- connections between course material

- coherence of arguments

- initiative

- contribution to dialog

- professionalism

Collaborative tests, sometimes called co-operative tests, are a student-centred, active learning approach to formal tests. Students complete their test in partners or small groups. Students learn by teaching others content during the testing session. Groups can vary between two and six students. Many variations of collaborative testing exist.

- Example 1: Students start independently, then join with a partner to discuss and adjust answers. Each student submits their own test.

- Example 2: Students work in assigned groupings and submit one test with all students receiving the same grade.

- Example 3: Double testing; students take test individually, then retake the same test with a group.

Collaborative testing supports inclusiveness and co-operative learning. This collaboration encourages active learning as group members discuss test questions, debate and problem solve to determine best answers and communicate supporting reasons for a particular answer. Collaborative testing can decrease pressure and anxiety within students, allowing them to show improved recall of material and improved test scores. Collaboration during testing alters the concept of competition among the students encouraging them to work together (Kennette, 2019), (Cantwell, et al., 2017).

A modification of a full collaborative test is the concept of test talks. In this process, students are given the first five minutes of the test period to talk with each other about the test questions while looking at the exam. No writing utensils are allowed. In general, students experience lower test anxiety and have rich conversations about content.

A test or exam wrapper is short student reflection task that occurs after an assessment (and sometimes prior to the assessment in addition). This writing activity asks students to review their study strategies in relation to their perceived performance on the assessment. The goal is for students to look ahead to future learning practices and to set appropriate goals for revision and success. Typically, a test wrapper includes questions that focus students on (Global Metacognition, 2020):

- how did you prepare for the test?

- what kinds of errors did you make on the test?

- how could you prepare differently next time?

The test wrapper can be supported through collaborative group discussion, bonus points for participation, or lesson on effective study techniques (Whitteck, 2022).

Open-book tests/exams are a method of assessing knowledge that allows students to use textbooks, class notes, the internet or other accessible reference material to complete the exam. The purpose is to assess higher order thinking rather than memorization. Open-book exams can be invigilated or students can have specified time to complete them.

When writing an open-book assessment, faculty must assume that students will have access to their notes, course materials and the internet. Questions should be designed so that the answers cannot be searched for online. It could include questions that ask students to link concepts or pose open-ended questions without one specific correct answer. Consider asking students to explain their thinking or a process. This type of questioning moves responses beyond the searchable response (UBC, 2022) .

A take-home test allows students to work on a summative activity that is demonstrating their knowledge, understanding and application of multiple concepts or learning outcomes. Take-home tests place the focus on assessing higher order thinking rather than memorization and recall. Questions can ask students to analyze, evaluate or synthesize knowledge, rather than just remember it. Take-home tests are in an unsupervised environment and students are usually given a specified time to complete the test (e.g. 24 hours). Typically, these tasks are not large projects, but an assessment that can be completed in a shorter timeframe, though they do require some consolidation of knowledge. There is some recognition that the results may not be as polished as a project that’s taken several weeks. Some examples (Diede, 2022) (Indiana University Bloomington, 2022) (UBC, 2022) (UC Berkeley, 2022) include:

- a poster/single presentation slide that summarizes the information from the section of the course

- a brief video in which students explain the course concepts in the unit or uses course learning to propose a solution to a given problem

- a concept map showing how the course content connects

- a problem to solve that requires combining knowledge and skills from the course

- an analysis of a data set or event combining knowledge from the course

- an infographic presenting the most essential course concepts/learning

- a case study analysis focused on key learning outcomes for course

- an annotated bibliography to support a learning outcome

- an executive summary or scientific abstract summarizing learning

- a reflection portfolio highlighting already submitted assignments reflecting course learning

- a reflection essay linking course concepts to learning outcomes

Moore (2018) suggests online/open-book assessments “should not be about improving performance of students taking them, but instead be about the authenticity to better prepare students for their world beyond university, thus encouraging better performance” (pg. 8). Consequently, open-book/take-home exams induce deeper learning, and provide students with opportunities to engage with contemporary workplace challenges.

More on open-book and take-home tests/exams

Here, you can find more information about the advantages, disadvantages, tips, best practices, academic integrity, and preventing plagiarism for open book and take home exams.

- Great for assessing higher-order learning, while de-emphasizing cramming or rote memorization

- Questions often are presented as problems or cases where students apply knowledge, analyze and/or evaluate information, or create something

- Questions can be longer and more involved and require students to integrate information from multiple sources or types

- Develops information literacy skills that emphasizes information retrieval skills and places greater focus on knowing how to use information

- Mimics professional work application of knowledge where information is available and the skill is in determining the appropriate application

- Provide opportunity for collaborative problem-solving and thinking

- Can decrease anxiety for some students

- Students may rely on their reference materials and not review or study as much

- Students may underestimate how long it will take to find resources to answer questions

- Students may be unfamiliar with the format and will need to be provided with clear procedures and rules See Tips for implementing online open-booked exams.

- Several types of questions that would be acceptable in a closed-book exam will not work in a open-book or take-home exams. These include questions that ask for definitions, descriptions or lists of properties, characteristics, etc. (Gupta, 2007 and Chan, 2009, as cited in Schwartz, n.d.).

Design exam problems that take advantage of the open-book format:

- Structure questions around problem-based or real-world scenarios that require students to “do things with the information available to them, rather than merely locate and summarize or rewrite it” (Chan, 2009, as cited in Schwartz, n.d.).

- Ask students to connect what they have learned in the course to their own lived experiences, observations, workplaces and communities

- Put an emphasis on the process, as well as the final product, by asking students to document their process verbally or visually (e.g. this could include a self-reflection component).

- Present “relevant qualitative or quantitative data and then ask students interpretative and application questions – What does the data show? What relevance does this data or does the scenario have in terms of [current topic]? What other factors could potentially affect this data? How would you test for these?”

- Test your questions by searching for the answer using a search engine such as Google. “If the question is written in such a way that it can easily be found by typing the question stem into a search engine, you will want to consider revising it” (University of Wisconsin).

- Make sure there is enough time allotted for the exam; open-book exam questions will typically take longer than closed book exams questions.

- Set up appropriate marking criteria or rubric with the weight placed on knowledge, comprehension and critical thinking, rather than just recall.

Questions in open book exams “need to be devised to assess the interpretation and application of knowledge, comprehension skills, and critical thinking skills rather than only knowledge recall” (University of Newcastle).

- Clearly define the learning outcome you want to assess. In other words, your questions should measure the skills or knowledge that students acquired as part of your course. Bloom’s Taxonomy of educational objectives can be used to design questions of appropriate difficulty. In open book exams, questions should ideally be at the levels of applying to creating.

- Keep the number of questions realistic and in line with the time limit of your exam and the grading required. Allow enough time to complete it with minimal stress, but not so much that they will obsess over their answers.

- Situate your question within a particular context, problem or situation. Ensure the context, problem or situation is clearly outlined for students.

- Use multilevel thinking, using questions that include phrases like “most appropriate” or “most important.” This approach forces students to make judgements and demonstrate a fuller understanding of concepts and the subtleties between different levels of correctness of the answers.

- Construct the question so that the task is clearly defined for students. Avoid passive sentence structure and ambiguous phrasing.

- Use directive verbs to clarify the types of thinking and content you require in the response. Refer to the directive verbs in the section on Higher-order question types above.

- Keep the number of questions realistic; with open-book exams, we might be tempted to give more questions.

- Consider alternative submissions, like creating a video submission where students record their answer.

Adapted from Adapted from (Concordia University, 2022).

- Decide whether all or part of an exam will be open book and let students know from the beginning of the course that this is the format you will be using.

- Establish what materials are permissible and how they will be selected. Ask yourself the following questions:

- What type of material can they bring or use?

- If it is an invigilated exam, how much can they bring?

- Will you check if the material are acceptable? Do they need to provide sources?

- How do you plan to guide students in the preparation of appropriate material? Bringing too much information with them will actually hinder their retrieval of the necessary knowledge.

- Be clear on evaluation expectations. For example, if students simply repeat what is in their class notes or on the internet, they won’t receive partial credit. See tips for writing open-book/take-home exam questions for more information.

- Discuss how each question will be evaluated (e.g. ideas, flow, writing style, etc.) and if you will be using a rubric to assign points.

In a systematic review published in November 2019, Bengtsson included a range of remedies from multiple research studies for decreasing plagiarism on non-proctored open-book and take-home exams.

You could use this as an opportunity to discuss academic integrity, asking all students to agree to an honour pledge that they will use only the approved materials. Introducing the idea of an honour code or honour pledge helps students to understand and make a commitment to academic integrity. This can support your discussion around the rules and procedures around citing sources and not engaging in practices of dishonesty. If the students co-develop the pledge, it can also create a sense of community and support students to have conversations between their classmates about academic integrity. For example, make the release of an exam contingent upon the student’s acknowledgement of an honour code such as the following:

Consistent with Georgian College’s Academic Regulations Academic Integrity, I agree that all the assignments, quizzes, project work and exams I complete will represent my work and my work only. I understand that all forms of academic misconduct are prohibited. I also understand that academic misconduct includes, but is not limited to, all forms of cheating, including the use of unauthorized materials, plagiarism, false identification, and forgery. In addition, I understand that it is my duty and my responsibility to familiarize myself with Georgian College’s Academic Regulations and inform the instructor if I become aware of any violations to this Honour Code.

| Remedy | Source |

| Questions are designed so that they require a thorough understanding of course material will be costly to “contract out.” | Bredon, 2003 |

| Ask for proof and justifications for all answers | Lopez et al., 2011 Svoboda, 1971 |

| Introduce an honour code | Fernald & Webster, 1991 Frein, 2011 |

| Grade down for answers without reference | Freedman, 1968 |

| Answers must make direct references to course-specific material | Williams & Wong, 2009 |

| Make questions highly contextualized (e.g. from the perspective of a particular character, during a certain time period, the impact in very specific circumstances/places, etc.) | Williams & Wong, 2009 |

| Randomly scramble the order of questions and answers. This is for open, multiple-choice questions. There is an option in Blackboard Quiz for this. | Frein, 2011 Tao & Li, 2012 Murray, 1990 |

| Ask for hand-written answers. You can ask students to take a picture and upload to Blackboard. | Lopez et al., 2011 |

Adapted from (Concordia University, 2022)

As with all types of assessment, students should have the opportunity to prepare and practise for open-book tests. Students need strategies to prepare for such an assessment. Here are some strategies for students to help prepare as well as some misconceptions that they should be made aware of:

- UNSW Sydney. (2022, March 24). Open-Book and Take-Home Exams. UNSW Current Students. Retrieved August 16, 2022

- Trent University. (n.d.). Preparing for an Online, Open-Book Exam. Academic Skills. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Anderson, L. & Krathwohl, D. (2001). A taxonomy for learning, teaching and assessing: A revision of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives. New York: Longman.

Campbell, N. (drsoup09). (2020, March 14). Take home exam overview and example. [Tweet]. Retrieved from twitter @drsoup09

Centre for Teaching and Learning. (n.d.). A guide for academics – Open book exams. University of Newcastle Australia.

Concordia University. (2022, May 6). Designing open-book exams. Centre for Teaching and Learning (CTL).

Moore, Chris, P. (2018). Adding authenticity to controlled conditions assessment: introduction of an online, open book, essay based exam. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 15(1), 1–8.

Schwartz, M. (n.d.). Open Book Exams. Centre for Excellence in Learning & Teaching, Toronto Metropolitan University.

University of Wisconsin Extended Campus. (2020). Unproctored Online Assessments.

Cantwell, E. R., Sousou, J., Jadotte, Y. T., Pierce, J., & Akioyamen, L. E. (2017). PROTOCOL: Collaborative Testing for Improving Student Learning Outcomes and Test‐Taking Performance in Higher Education: A Systematic Review. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 13(1), 1–18.

Carnegie Mellon University. (2022). Using Concept Tests. Eberly Center. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Diede, M. (2022, May 4). Alternatives to Traditional Exams. Answers – Syracuse University. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Global Metacognition. (2020, January 10). Do Exam Wrappers Work? The Global Metacognition Institute. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Indiana University Bloomington. (2022). Alternatives to Traditional Exams and Papers. Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Kennette, L. N., PhD. (2019, July 12). Variations to Traditional Multiple-Choice Testing. Faculty Focus | Higher Ed Teaching & Learning. Retrieved August 16, 2022

UBC. (2022, July 20). Assignments & Assessments. Keep Teaching. Retrieved August 16, 2022

UC Berkeley – Research, Teaching, and Learning. (2022). Alternatives to Traditional Testing. Berkeley Center for Teaching & Learning.

University of Houston – The Honors College. (2022, January 10). The Oral Final. University of Houston. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Whitteck, E. (2022). Exam Wrappers. Piktochart Visual Editor.

Adapting questions to individualize test-like assessments

To promote academic integrity on test-like assessments, faculty can consider adapting traditional type questioning to promote individualized answers. For an overview of creating exams, review this page from the Eberly Center (Carnegie Mellon University, 2022).

Reflection-type questions have students explore their learning journey and link course topics to real-life situations. By asking students questions about their individual virtues and real-life situations, some of the essential employability skills and learning outcomes for the course can be assessed (Lawrence & Vrhovnik, 2022). The table below examines various personal virtues and provides examples test questions highlighting each virtue (adapted from (Su, 2020)).

| Virtue | Example |

| Persistence | Take one quiz or practise problem or concept you struggled with this semester and explain how the struggle itself was valuable. Describe the struggle and how you overcame it. How might this experience benefit you in your career? |

| Strategization | For any question you cannot answer on this exam, suggest a strategy you might try to solve or answer the question. Describe any gaps you are unable to bridge and list three helpful insights that may help another person trying to answer this question. |

| Thinking for oneself | Choose one interesting concept or problem from the course resources that was not assigned/discussed. Describe why you find it interesting. Write two multiple choice or annotated true/false questions that could appear on a test for this topic. |

| Curiosity | What course related idea or concept are you curious to know more about as a result of taking this class? Give example and describe why this is interesting to you. |

| Imagination | How has your math/science/course topic imagination been enhanced as a result of taking this class? |

| Disposition toward beauty | Consider one idea from the course that you found beautiful and explain why it is beautiful to you. Your answer should be understandable to someone who has not taken this course. |

| Creativity | Give one example from this course content that you found creative and explain what you find creative about it. It could be something personal or your experience with a topic. |

Students can be part of the assessment generation process. Faculty can consider using test questions that students have developed on their own. This process encourages students to think in-depth about a concept, evaluating potential ways to test the concept and to think through the correct answer and evaluation (Kennette, 2019). Questions can be generated as part of a classroom learning activity or as part of an assignment for a particular chapter or concept.

Having all students complete the same questions on a test-like assessment leads to little opportunity for variation or personal choice. When creating a test, offer students some choice on which test questions they would like to answer. By providing this option, the faculty increase assessment accessibility for all students. This can be done with all types of questions, including short-answer and multiple-choice questions (Kennette, 2019). Remember to give some consideration to value of question options so that the test total does not change between students. In addition, correlate question options to learning outcomes to ensure all students are being assessed fairly.

Multiple-choice questions are typically used when testing large groups of students or large amounts of content. Automated grading can be done through the learning management system or a mechanical grading software (Indiana University Bloomington, 2022).

To increase student’s cognition when answer multiple-choice questions, consider having students do the following with a selection of questions:

- Rank multiple-choice responses from correct to somewhat correct to most incorrect. Have students write explanations to support their ranking. Allow opportunity for discussion and debate amongst peers (Harvard, 2020a).

- Interact with all responses by having students indicate why might someone choose this incorrect answer, rewrite the question to make this answer correct, provide an illustration or memory aid to support the response (Harvard, 2018).

- Confidence weight multiple-choice answers. Have students select the correct answer indicating complete confidence or select an intermediary point between two answers indicating uncertainty (Harvard, 2020b).

- Explanation of multiple-choice answer where students explain why their answer is choice is correct or why the alternative answers are wrong.

True and false questions are prone to misinterpretation and literacy challenges resulting in students guessing which gives them a 50:50 chance of the correct answer. One method to improving these types of questions is to have students change false statements to make them true. The student indicates whether the statement is true or false. If false, the student must change the underlined word or statement to make the statement true. Here is an example (Cloud County Community College, n.d.):

- Example: T F _electrons________ 1. Subatomic particles of negatively charged electricity are called protons.

Another option is to use items that require cause and effect. The statement has two parts, both of which are true. The student must decide if the second part explains why the first part is true. Here is an example (Cloud County Community College, n.d.):

- Example: Yes No 1. Leaves are essential because they shade the tree trunk.

Short-answer questions are open to lot of potential variety and individualization. Here are some ideas (Indiana University Bloomington, 2022):

- Have students write a meaningful paragraph given a list of specific terms that must be used to demonstrate their understanding of terms and interconnections.

- Change multiple-choice questions into short answers questions to have students show their understanding of key concepts.

- Setup a series of short answer questions based on a real-life application of the topic or content. The questions are linked through the application but independent of each other. This creates more of a story and encourages in-depth analysis and application.

Using Blackboard, Georgian’s Learning Management System (LMS), faculty can add individualization to online tests and quizzes. Here are some ideas. For more support, visit the Centre for Teaching and Learning.

- Randomize question order in test

- Use pools/banks for each question block so that each student gets a different selection of questions

- Use calculated questions so each student gets unique numbers

- Use short answer for more open-ended questions

- Randomize multiple-choice option order but watch out for questions that say “all of the above” or similar

- Use file response options and have students handwrite answers with their signature and snap photo to upload

- Break test into parts; student must complete one part before starting next and use adaptive release so parts aren’t visible

Carnegie Mellon University. (2022). Creating Exams – Eberly Center – Carnegie Mellon University. Teaching Excellence & Educational Innovation.

Cloud County Community College. (n.d.). How to Write Better Tests.

Harvard, B. (2018, May 15). Maximizing the Effectiveness of Multiple-Choice Qs. The Effortful Educator.

Harvard, B. (2020a, April 27). Ranking Multiple-Choice Answers to Increase Cognition. The Effortful Educator.

Harvard, B. (2020b, June 22). Confidence Weighted Multiple-Choice Questioning. The Effortful Educator.

Indiana University Bloomington. (2022). Alternatives to Traditional Exams and Papers. Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Kennette, L. N., PhD. (2019, July 12). Variations to Traditional Multiple-Choice Testing. Faculty Focus | Higher Ed Teaching & Learning. Retrieved August 16, 2022

Lawrence, K., & Vrhovnik, K. (2022, June 10). Reflection as an assessment for quantitative courses like Statistics? Yes we can! [Slides]. Advanced Learning 2021.

Su, F. (2020, April 28). 7 Exam Questions for a Pandemic (or any other time). Francis Su.